Certificate authorities aren't responsible for phishing

Phishing sites have valid certificates and that's how it should be. Here's why universal HTTPS matters more than identity verification.

I saw a post on LinkedIn about URLs that look legitimate but lead to phishing sites. Someone commented: “The green certificate color indicates the attacker went through a certificate authority. This raises questions about that organization’s responsibility.”

No. That’s completely wrong, and this misconception needs to die.

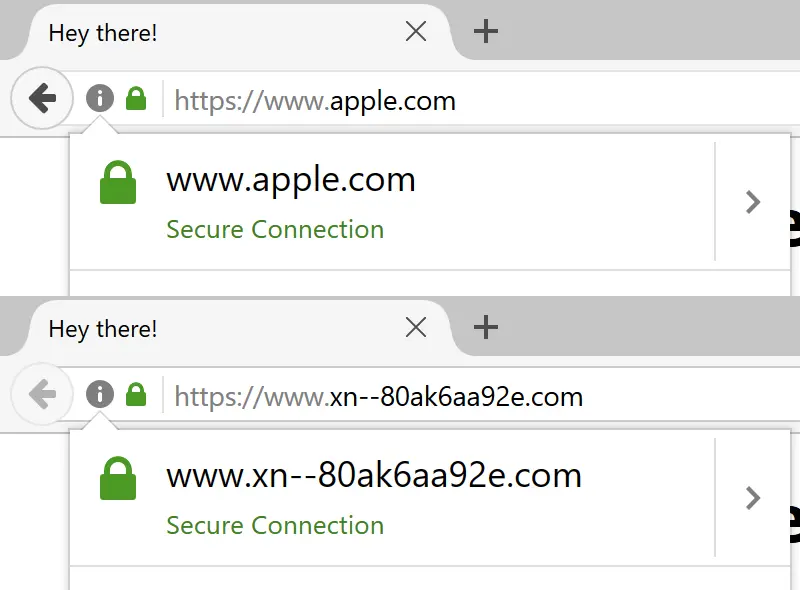

You click on https://www.google.com/ and land on a phishing site. The URL bar shows exactly what you expect. The padlock is there. Everything looks perfect.

Except it’s not Google.

How homograph attacks work

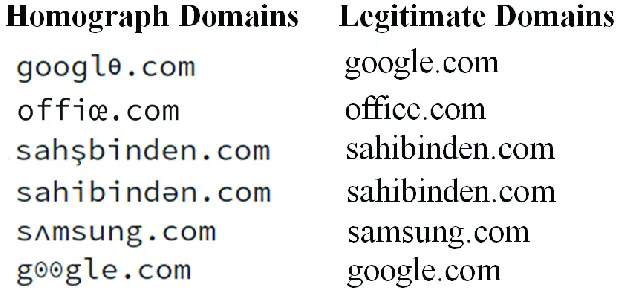

The attack uses Unicode characters that look identical to Latin letters. Greek ο instead of o, Cyrillic а instead of a. An attacker registers gοοgle.com with Greek omicrons. Your eyes see “google.com”. DNS sees something else entirely.

The padlock is not the problem

The phishing site has HTTPS and a valid certificate. That’s exactly how it should be.

Domain Validation (DV) certificates verify you control a domain. They encrypt traffic. They don’t verify identity.

Before Let’s Encrypt, certificates cost money and took days. Most sites ran on HTTP. Your passwords and credit cards traveled in cleartext, visible to ISPs, WiFi hotspots, governments.

DV certificates fixed this. Free, automatic, instant. The entire web got encrypted! One of the most important security improvements in internet history.

Blaming CAs for issuing certificates to phishing domains is like blaming the post office for delivering scam letters. They verify the address exists, not that the sender is trustworthy.

HTTPS means encrypted connection. It never meant safe destination.

OV and EV certificates exist for this reason

Organization Validation (OV) and Extended Validation (EV) certificates verify the legal entity behind a domain. The CA checks business registration, physical address, sometimes even calls a representative.

European qualified certificates go further with strict eIDAS requirements.

The problem: browsers stopped differentiating them in the UI. Chrome removed the green bar and company name from EV certificates in Chrome 77 (September 2019). Firefox followed with version 70. Google’s reasoning: the EV indicator “does not protect users as intended” and security research showed it didn’t prevent phishing. Users can’t tell the difference at a glance anymore.

So we have identity verification infrastructure that browsers don’t surface. Great!

Browser mitigations

Modern browsers convert suspicious IDN domains to Punycode in the URL bar. That gοοgle.com with Greek characters displays as xn--ggle-0nd.com.

This works when the entire domain uses non-Latin scripts. It fails when attackers mix scripts cleverly. Some combinations slip through.

Firefox lets you force Punycode display for all IDN domains in about:config with network.IDN_show_punycode = true. Ugly but safe.

Practical defenses

Use bookmarks for sensitive sites. Don’t click links to your bank. Type the URL or use a bookmark. This single habit blocks most phishing.

Password managers won’t autofill on fake domains. The manager sees the real domain, not the visual representation. If it doesn’t offer to fill credentials, something’s wrong.

Check the certificate manually. Click the padlock, view certificate details, look at the actual domain. Tedious but definitive.

Enable MFA everywhere. Stolen credentials are useless without the second factor. Not perfect protection but significant friction for attackers.

Enterprise: block IDN domains. If your users don’t need internationalized domains, block them at the DNS or proxy level. Blunt but effective.

The real issue

Technical mitigations exist. They’re incomplete and inconsistent across browsers. The fundamental problem is that URLs were designed for machines and we ask humans to verify them.

Phishing works because we trust what we see. Homograph attacks exploit that trust at the character level.

No amount of user education fixes a system where the security-critical identifier is visually ambiguous. We need browsers to surface identity information better, or we need to stop pretending URLs are human-readable security indicators.

Until then: bookmarks, password managers, MFA. Assume every link is hostile until proven otherwise.

Enjoyed this article? Share it!